Grand Strategy: These BRICS can’t construct a new world order

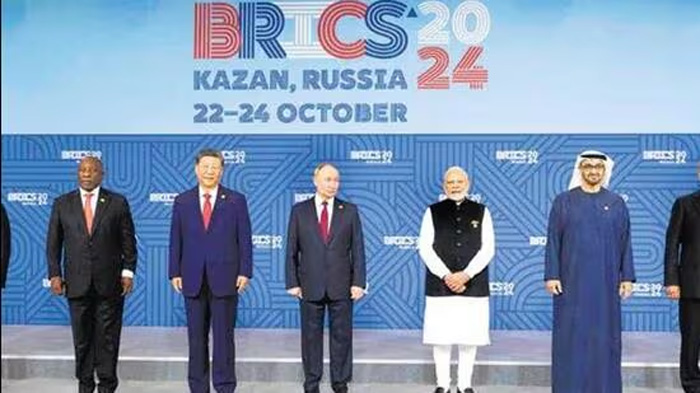

The recently-concluded BRICS summit in Kazan, Russia, along with its symbolism and the 143-paragraph declaration reflects the sharpening geopolitical faultlines across the world, and the group’s diminishing utility for India’s interests.

More importantly, the new BRICS – or BRICS 2.0 – doesn’t appear to be in a position to help reform the current world order or construct a more egalitarian one. For one, the ability of any one country or bloc to effect structural changes without a global consensus remains severely limited today. Secondly, I remain unconvinced that the primary objective of major BRICS countries, except for states like India, is to engage in serious and sober negotiations to bring about institutional reforms. Thirdly, considering the state of relations between the status quoist West and the US on the one hand, and revisionist powers like Russia, Iran and China on the other, it would be naïve to believe that the two sides would engage in a consultative process for meaningful reforms.

This poses a major challenge for India considering that contemporary India, unlike during the Cold War years, believes in reform rather than revisionism in the global arena. For India—neither fully status quoist nor revisionist—a middle path is inherently preferable, a stance not shared by its key BRICS partners.

BRICS and its growing contradictions

BRICS 2.0, in its quest to become a major global counterpole to the US-led order, is fraught with several challenges and contradictions. For one, its members hold contradictory views about the global order – while countries like India seek reform, China, Russia and Iran might not. This is perhaps the reason Saudi Arabia has so far declined to accept the invitation to join the grouping. Moreover, true to the nature of BRICS 2.0, we are likely to witness a sharpening anti-West rhetoric from its statements. Ironically, however, the sharper the BRICS summit declarations sound, the lesser it would be able to inspire global institutional reforms. The more it sharpens its language against the West and the US, the less it would serve India’s geopolitical interests, and the less it serves as a platform that can encourage global structural reforms, the more India is likely to be disenchanted with the new BRICS. New Delhi has instrumental expectations from the BRICS, not ideological.

This also points to another related challenge – that is, diminishing internal cohesion among its members considering the divergent geopolitical ambitions of the new members as well as those seeking its membership.

Another potential point of contention among the BRICS members is regarding its consistent amplification of the concerns of the global South. This is problematic for several reasons. Neither are Russia and China members of the global south, nor are the Chinese and Indian visions for the global South align. While China seeks to cultivate a support group in the global south in its efforts against the US-led world order despite being a major stakeholder in such an order, India seeks to be a bridge between the developed north and impoverished south even though it is not a major beneficiary of such an order. Their world views couldn’t be further apart: One seeks to bring the North and South closer, and the other seeks to keep them apart.

Are all BRICS members genuinely committed to a reformed world order? Perhaps not. Consider this. While the founding premise of BRICS remains valid – that developing countries need greater representation in global politics. However, China—one of the bloc’s founding members—remains the biggest obstacle to the integration of India, its fellow founder, into international institutions. Can a grouping, whose members actively stop each other from gaining more representation in multilateral organisations, make a credible claim that it is serious about creating a more representative world order?

Limits of rhetoric

From an Indian perspective, BRICS has limited material value. For sure, it has benefitted from the BRICS development bank, helped India asset itself as a major non-Western power, and join forces with other non-Western powers to function as an influential actor in world politics, at least in terms of perceptions. But the expansion of the BRICS may go on to undo that for New Delhi.

Moreover, while the rhetorical tools adopted by the BRICS helped India in the past gain more leverage with the West and the US, the shrill rhetoric from BRICS 2.0 today might not help India’s cause. BRICS as a wannabe counterpole in world politics helped India’s interests. With new members and more seeking entry, BRICS 2.0 might actually become a counterpole—and that could be a problem for India. Rhetoric loses its utility when it’s taken seriously.

The very fact that BRICS leaders sign on to grandstanding summit declarations is also because they understand their inherently inconsequential nature. The grander the declaration, the lesser its impact. The more signatories realise its limited impact, the more likely they are to issue a grand statement; and the more they think it’ll be consequential, the less likely they are to engage in grandstanding.

Let me conclude by making two points. One, while multi-alignment is an important strategy for India in an unstable world order, the question before us is this: what kind of a power does India want to be? If India aspires to be a major global actor, taken seriously by other powers, and capable of shaping the international order, it must ask whether BRICS 2.0 can truly advance that goal.

Two, as I pointed out above, there is a reason why BRICS-like groupings exist: to seek greater representation for developing countries in global politics. For sure, this underlying rationale of the BRICS is both laudable and must not be lost sight of. And yet, New Delhi would do well to refuse to allow the vehemently anti-Western voices in BRICS 2.0 to hijack the global South Agenda for their narrow geopolitical purposes.

While anti-Western narratives could serve as a smart opening move for India, it can’t be the main play in India’s grand strategy towards the international system.